Mindweather 101: A powerful class for the many beautiful people tormented by their own mind

This All of Life course Thomas McConkie and I created about "navigating mental and emotional distress"is still one of the best online mental health classes out there—available at no cost below.

Sometimes the weather is sunny. Sometimes it’s stormy. And sometimes a tornado hits.

That’s kind of how our mind and heart are too. Depending on the day, and even the moment, different thoughts and feelings come and go like weather patterns in the sky. At certain points, the mind and heart can be pushed so far that extreme mental and emotional states arise. What to do then?

“I was so devoid of hope—so devoid of hope—and felt so alone . . . my world had become so small that I didn’t see any light at the end of the tunnel,” a woman told us about her experience with emotional struggles.

“When you’re actually in these negative storms that can last months and even years,” said University of Miami cognitive neuroscientist Amishi Jha in an interview, “it’s very hard to think that it’s possible to step outside of it. It is your world.”

In this class, we use the word “mindweather” to capture the wide spectrum of mental and emotional experiences we experience as human beings.

Do mental or emotional problems have to feel this hopeless—in a way that they dominate and control our lives?

“My life really had shrunken to the point where I just saw myself as mostly this mentally ill person who would be dependent on psychiatrists and therapists to get through life,” another woman said. “I was told by one professional, ‘Maybe one day you’ll get your life together enough that someone will marry you. . . . Maybe you’ll have a job one day.’”

This class was designed to speak to that woman or man, and to the many people who love this individual desperately. Along with this other preview of the class, we created this trailer on “learned hopelessness.”

The last 30 years have seen literally tens of thousands of research studies emerge on the roots of this pain—and ways people might find their way to deeper, more sustainable healing. That’s what you’re going to hear about in this class - something Clay Olsen and I elaborate in our new book coming out this year too.

The insights and patterns we review are broadly applicable across a wide range of conditions, from depression and anxiety, to ADHD, eating disorders and even delusion/schizophrenia.

Introspective, not prescriptive

Our aim is certainly not telling you what to do or making specific recommendations about your situation necessarily. Those are questions only you can settle for sure, with your loved ones and any professionals you trust along the way.

Instead, our aim in this class is simply to help you think more carefully about some of the core questions and issues at the heart of mental and emotional disorder.

Outline

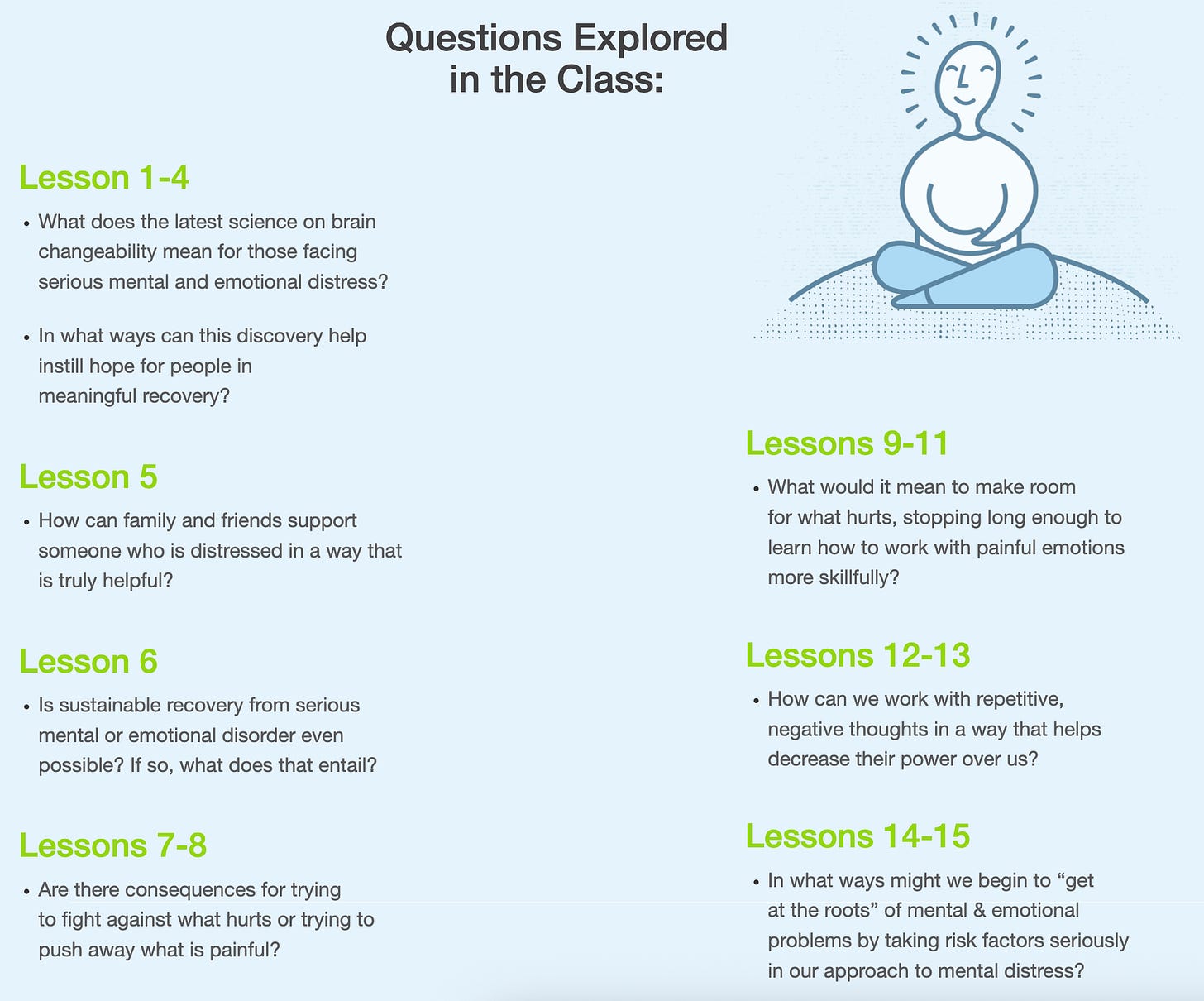

As detailed in an introduction video (that you can probably skip because you’re reading this), the class exploration will center around two key questions currently being asked by millions facing these problems: First, where are these problems coming from?

Secondly: How can we best respond to, and attempt to work with these kinds of mental and emotional problems? What kind of help can I offer my friend, family member—or myself—to really start feeling better: and not just for a good week or two. The rest of the course covers this ground.

Be patient, go gradual + maybe, don’t skip?

Some of this material will stretch you. And that’s why we don’t rush through it - giving it time to really allow you to absorb it. This means it’ll take a little more patience…especially when that voice says “I want to do this at double speed!”

You may wonder about trying to get through the whole class in one day. We don’t recommend that. You may also be tempted to skip ahead. Since the later lessons build on earlier ones, we recommend you take the class sessions in order.

A team of teachers

Alongside Thomas McConkie and Vicki Overfelt, two remarkable mindfulness teachers, I will be one of your guides for the class. We’ll also be hearing from nearly thirty-five other researchers and professionals we hand picked, as well as individuals who have found deeper emotional healing.

Special thanks to Utah Youth Village who provided support to make it possible to complete these interviews. Patrick David Jennings did incredible work on the editing of these classes, with huge gratitude to him and his father, David. Also, I so appreciate the late Kevin Reem, a wonderful man who worked at Disney and loved his daughter who struggled emotionally, who organized the professional film shoots at several different locations. My brother Daniel Hess also provided wonderful footage from a conference in Syracuse, New York.

Accessible for anyone

Along the way, we do our best to avoid unnecessary jargon or scientific language and give it to you straight, with a short glossary of more complicated terms referenced here:

Thank you for joining us. What you’re about to see is the product of thousands of hours of effort, across hundreds of hours of interviews, and based on the hard work of twenty volunteers—including Yvonne Jacobs, whose hand transcription for the entire course is available below:

MAKING SENSE OF THE PROBLEM

In the first couple of lessons, we’ll start exploring some discoveries about the brain— breakthroughs that, surprisingly, very few people still seem to know about.

Lesson 1. The brain’s role in mental distress: One view

For much of the last century, mental and emotional distress has been understood through the lens of a fixed, unchanging adult brain—one that is permanently wired and prone to lifelong malfunction. While this view has helped validate suffering as “real,” it has also quietly shaped how people see themselves and their future.

Review:

The brain plays an important role in mental and emotional distress.

Historically, there have been very different ways of thinking about that role.

One of them is that the adult brain is largely fixed and unchanging over time.

Reflection + Discussion:

What have you been told about the role of the body or brain in your own condition, or that of your loved one?

Were you ever told by friends, family or professional help, that your brain or body was permanently disordered in some way?

Why do you think the “fixed brain” model became so dominant in modern culture?

Lesson 2. What we believe about the brain matters: Believing your brain is broken makes a difference.

Believing the brain is permanently broken or deficient can deeply shape how people see themselves, often reinforcing hopelessness and a narrowed sense of what life can become. These beliefs don’t just describe suffering—they actively influence motivation, identity, and the possibility of recovery.

Review:

The brain matters.

What we believe about the brain matters too.

Believing the brain is permanently deficient can make some people feel even more hopeless.

Reflection + Discussion:

How have ideas about a “broken” or “defective” brain affected your own feelings of hope in the future? How might those stories affect someone already feeling vulnerable or discouraged?

In what ways might this message help people (reducing blame)—and in what ways might it unintentionally harm? Why might messages meant to be “realistic” sometimes feel crushing?

What responsibility do helpers have in how they talk about the struggle and the future prognosis? Where do you see the line between validating suffering and unintentionally limiting someone’s future?

There is a growing scientific literature that explores the power of belief and expectation in the progression of healing and recovery—including something called the “placebo effect.” Essentially, what we’ve just reviewed above is a kind of reverse placebo effect.

Lesson 3. The brain’s role in mental distress: Another view

Modern neuroscience has revealed that the adult brain is not fixed, but continuously changing in response to experience—a capacity known as “neuroplasticity.” This discovery reframes mental distress not as permanent damage, but as patterns that can evolve, adapt, and reorganize over time.

Review:

The brain is super-important.

Scientists used to believe it was permanent when we became adults.

Now they don’t.

Reflection + Discussion:

When was the first time you heard about neuroplasticity?

Why do you think it’s taken so long for the public awareness to grow about this hopeful discovery?

In what ways could this view influence how society responds to mental health challenges? How might this understanding shift mental health policy or treatment priorities?

Lesson 4. What we believe about the brain matters: Believing your brain is changeable-healable makes a difference.

Understanding the brain as changeable can restore hope, soften identity labels, and expand how we explain mental and emotional suffering. This shift opens the door to seeing distress not only as an internal flaw, but as something shaped by experience, environment, and meaning.

Lesson 4, Part 1

Lesson 4, Part 2

Review:

What we believe about the brain matters.

This belief can make a difference for how we see ourselves.

And it can even determine whether recovery seems possible at all.

Reflection + Discussion:

What does this other understanding of the brain mean for individuals and families facing serious mental and emotional problems? What feelings arise for you personally when you hear that the brain can change over time?

How does seeing the brain as changeable alter the way you view yourself—or someone you love?

How does this perspective change the way you think about long-term possibilities? What possibilities feel newly open—or still hard to believe?

In these first four lessons on the brain, we’ve tried to lay out a simple, clear exploration of competing brain narratives, and what they might mean for people’s actual experience of mental illness and recovery.

As you can see, the way we talk about the brain can have vivid, real-life consequences for actual lives—including how and whether people feel hope for a future that looks better—really better—than today.

Obviously many questions remain. For example, what exactly does recovery look like? (soon) And, how can friends and family best support someone facing emotional burdens?

Lesson 5. Just being there: Insights for family and friends.

Healing does not belong exclusively to professionals—authentic presence, listening, and human connection of any kind can be profoundly therapeutic. Often, what helps most is not fixing or solving, but staying close without an agenda and allowing someone to feel less alone.

Lesson 5, Part 1

Lesson 5, Part 2

Review:

Professionals can be very helpful.

So can family and friends...but that can be easy to forget.

In either case, there is surprising power in dropping the agenda and fully being with someone.

Reflection + Discussion:

When someone you love is hurting, do you feel pressure to fix—or permission to simply be with them?

What forms of presence have helped you most during your own emotional struggles?

How can ordinary acts of connection quietly support recovery?

In the next class discussion, we’ll take another look at recovery itself—exploring competing views of what exactly that means.

Lesson 6. Different ways of thinking about recovery

While recovery is often defined narrowly as lifelong symptom management, research and lived experience show that deeper, more meaningful recovery is possible—even after severe distress. Rather than a straight line, recovery tends to unfold slowly, unevenly, and through renewed connection, purpose, and hope.

Lesson 6, Part 1

Lesson 6, Part 2

Watch for this quote! “You have a well part in you . . . and it’s a beautiful part. Never forget that.”

Review:

There are very different ways of thinking about recovery.

Many believe full recovery is not possible—seeing long-term symptom management as their best hope.

Others believe full recovery is indeed possible...because they have lived it.

Reflection + Discussion:

How have you personally or in your family defined recovery from mental or emotional challenges? Do you believe recovery should be seen as coping, functioning, or something deeper?

How does the idea of recovery as a gradual, non-linear process land with you?

What would “a life of meaning and belonging” look like beyond symptom reduction?

RESPONDING TO THE PROBLEM

Lesson 7. One way of responding to mental distress

One common way people respond to emotional pain is by distracting, avoiding, or numbing it—through sleep, substances, busyness, screens, or other forms of escape. While these strategies may offer short-term relief, over time they fail to address the roots of distress, while quietly creating new problems of their own.

Lesson 7, Part 1

Lesson 7, Part 2

Review:

One way to respond to emotional pain is to distract, avoid and numb out.

This is something we all do sometimes.

While it might provide some relief in the moment, over the long-term this approach may not get to the bottom of our problems.

Reflection + Discussion:

What are some common ways people—individually or culturally—try to make emotional pain go away quickly?

Why do avoidance strategies make so much sense in the moment, even when they don’t work long-term? In what ways might our culture reinforce the belief that pain should disappear immediately?

How can avoidance unintentionally turn into a habit or pattern over time?

If it’s true that avoidance doesn’t actually get to the bottom of our problems and may sometimes complicate things, why do we keep going back to ways to avoid or distract from our pain?

Before moving on, here’s a short video summarizing this lesson’s key point, in case you find it helpful or would like to share with someone:

Lesson 8. Can trying to ‘make it go away’ make it worse?

Efforts to force painful thoughts or emotions to disappear can sometimes backfire, intensifying distress rather than relieving it. When people fight their inner experience too aggressively, they may unknowingly strengthen the very patterns they are trying to escape.

Lesson 8, Part 1

Lesson 8, Part 2

Review:

Trying to make pain go away immediately may have some effects in the short-term.

Over the long-term, however, two problems often arise:

Deeper problems are not fully resolved.

Problems can get worse, as the consequences of short-term efforts pile up.

Reflection + Discussion:

Have you noticed situations where trying harder to feel better actually made things worse? More specifically, have you ever noticed things getting worse after some kind of attempt to make pain or distress go away?

Why might the mind react negatively to pressure—even pressure meant to help?

As we learn to stop resisting so much, we may find ourselves having much more energy to meet the challenges of life more effectively. If you listen deeply in this moment, can you detect anything in your life that you might have been resisting?

We’ve highlighted in this discussion some of the consequences of trying to fight against what’s happening in our heads. For one, this probably won’t make the problem go away. What’s worse, fighting our thoughts or feelings can also give problems more power and potentially make the situation worse (here’s two quick summaries of the main point of this lesson if it’s helpful, or you’d like to share them with others).

In the end, the need to avoid pain can become a festering problem in itself. In the next lesson, we’ll begin to explore another approach.

Lesson 9. Another way of responding to mental distress

Instead of fighting or fleeing painful experience, another approach involves stopping, paying attention, and meeting distress with gentle awareness. By staying present with what is—without judgment or force—people often discover new flexibility, choice, and unexpected paths toward healing.

Lesson 9, Part 1

Lesson 9, Part 2

Lesson 9, Part 3

Review:

It’s possible to approach emotional pain in a more gentle way.

As we fight less against our pain, we notice that we suffer less.

By making room for whatever is coming up in our lives, a new sense of possibility and freedom can arise.

Here’s a short video summarizing the key point, in case you find it helpful or would like to share with someone:

Reflection + Discussion:

What reactions come up when you hear about this idea of “staying with” emotional pain rather than only avoiding it? Why might stopping and observing feel counterintuitive—or even frightening—at first?

How is acknowledging pain different from giving up or resigning yourself to it?

What does it mean to relate to thoughts and feelings as experiences, rather than as commands?

What do you notice when you stop and observe what is going on inside? How might awareness create space for choice, even when circumstances don’t change?

What feels hardest about simply allowing discomfort to be present, even briefly? Where in everyday life might small moments of presence be possible?

Mindfulness supplement to Lesson 9

So what is this mindfulness stuff anyway? Can someone give me a definition? This supplemental video dives in more directly into what exactly mindfulness is.

Lesson 10. Surrounded with gentle acceptance: More for family and friends

Family and friends often respond to a loved one’s suffering with urgency, fear, or a need to fix—yet these reactions can unintentionally increase pressure and distress. A more healing stance involves patience, acceptance, and presence, allowing the person who is suffering to heal in their own way and at their own pace.

Lesson 10, Part 1

Lesson 10, Part 2

Review:

With good intentions, sometimes we try to do something to make the pain of our loved ones go away.

This can sometimes make things worse for our friends or family.

By being gentle and accepting with someone—no matter where they are—we invite them to be gentle with themselves.

Reflection + Discussion:

Why is it so hard to sit with someone else’s pain without trying to fix it? How might good intentions sometimes create additional pressure for someone who is struggling?

What does “being present” actually look like in your own relationships? How can acceptance coexist with hope for change?

In what ways might gentleness restore dignity and motivation more effectively than control?

How could slowing down change the emotional climate in families or communities under stress?

Lesson 11. Can a gentle approach make a difference for mental and emotional pain?

Approaching emotional pain with gentleness, awareness, and compassion—rather than resistance or control—can fundamentally change how that pain unfolds. Research and lived experience suggest that when emotions are allowed to arise and pass naturally, suffering often decreases, while the brain is allowed space to gradually reshape itself in healthier ways.

Lesson 11, Part 1

These ideas can be fresh and exciting for some—and a bit unsettling and confusing for others. Take whatever time you need with them. There is no rush!

Lesson 11, Part 2

Review:

A more gentle and accepting approach to our emotional pain can have some surprising results.

For instance, we can begin to notice pain passing and changing on its own.

As we practice being more gentle, we get better and better at working with whatever comes up in our lives—no matter what it is.

Over time, this approach helps the brain change in positive directions.

Reflection + Discussion:

What do you usually try to do when emotional pain shows up—fight it, fix it, escape it, or something else?

Why might gentleness feel counterintuitive—or even risky—when emotions are intense?

Have you ever noticed a difficult emotion soften or pass on its own when you stopped struggling with it?

How does the idea that emotions are temporary “events” rather than permanent truths change how you relate to them?

What feels hopeful—or challenging—about the idea that the brain can change through how we pay attention?

What might it look like to meet your own pain (or someone else’s) with a little more patience and compassion this week?

Before moving on, here’s two short videos summarizing the key points: “Making Room for What Hurts” and “Witnessing the Storm.”

From individual experience to the brain itself, the consequences of learning this other approach to painful emotions and thoughts are real. This is no snake oil. We’re talking about something with hard data and good evidence showing it works.

In the next lessons, we’ll consider what this approach means for something like thinking itself.

WORKING WITH DIFFICULT THOUGHTS

Lesson 12. One way of thinking about thinking

Many people relate to their thoughts as if they are facts or direct reflections of reality, which can make distressing thinking feel overwhelming and inescapable. When thoughts are taken literally and examined endlessly, they often lead to rumination—intensifying anxiety, depression, and emotional suffering rather than resolving it.

Lesson 12, Part 1

Lesson 12, Part 2

Review:

When we get caught up in our thoughts, life becomes distorted.

This can cause a lot of suffering.

We can learn to relax, step back from thinking, and start to feel more content.

Reflection + Discussion:

In what ways do people tend to assume their thoughts are true, and a reflection of reality or “who they are”?

Why might trying to “think your way out” of emotional pain sometimes make things worse?

What costs—emotionally or physically—come with staying stuck in your head?

Wouldn’t it be nice to learn how to step away from that cycle, and even find some peace? The message of this lesson is that analyzing and over-analyzing may not be the best strategy to get there.

The message of the next lesson is, simply put: there’s another way.

Lesson 13. Re-thinking thinking

A different relationship to thoughts becomes possible when we learn to observe them as passing mental events, rather than facts we must believe or act on. By stepping back and watching thoughts come and go, we gain space, choice, and freedom—often reducing distress and opening the door to more lasting change.

Lesson 13, Part 1

Lesson 13, Part 2

Lesson 13, Part 3

Review:

The mind offers up thoughts for us to consider.

We can practice choosing which thoughts we want to “grow” and attend to.

As we get better at this, we feel happier and freer.

Reflection + Discussion:

Have you ever noticed a thought lose its power once you simply observed it?

What kinds of thoughts tend to pull you in most strongly?

What changes for you when you consider thoughts as experiences, not simply as truths?

Why might focusing on the body or breath help loosen the grip of thinking?

How does it feel to imagine having a choice about which thoughts you engage with?

In summary, we’re not doomed to our dark, negative and destructive thoughts. There is life beyond. Although it can be challenging to apply and practice, the benefits for learning this skill are well worth it. As you explore this for yourself, be patient with yourself, have some fun, and good luck!!

BROADENING THE CONVERSATION

We started the course exploring how to make sense of mental and emotional distress—exploring two ways of understanding the brain’s role. For those people who see the brain as permanently deficient, there will naturally be limits to what they come to hope for in terms of recovery. (After all, even if there are other things that can be done to support recovery, the fact remains: the brain still has a permanent deficiency).

But what happens when that’s not a fact anymore? As people become aware of brain changeability, we’ve noticed at least two things start to change: First, all of a sudden, new hope begins to emerge for deep and lasting recovery from mental disorder as a possibility for literally anyone—not just those who don’t have it very bad. And secondly, the wide range of contributors to mental disorder become more relevant—inviting us to look more deeply at all of life—the social, relational, cultural, and environmental conditions that can either intensify distress or support healing.

Lesson 14. Exploring the full range of contributors to mental/emotional distress

To understand mental and emotional distress, to really get at the roots of these kinds of challenges, we need to look beyond the biology and chemistry of individuals alone and start looking at the full range of life: All of life. That means surveying the variety of factors that can contribute to or subtract from our mental health. The environment we live in is an important place to start.

Lesson 14, Part 1

Lesson 14, Part 2

Review:

There is likely no single and solitary “cause” of mental/emotional distress.

Current research, instead, confirms lots of diverse contributors.

That’s actually pretty good news!

Reflection + Discussion:

Why do you think we’re drawn to single-cause explanations for complex struggles like depression, anxiety, or ADHD?

What are a few “hidden contributors” people often overlook (sleep, pace of life, isolation, screen exposure, food, stress load, etc.)?

How does it change things to hear, “Your feelings may be an understandable reaction to an abnormal situation”?

Depression + ADHD risk factor questionnaires

The majority of mental health questionnaires focus on symptoms—the observable, behavioral manifestations of how someone is currently feeling. While this is an important aspect of any experience to consider, we typically end up paying far less attention to the root risk factors of what is going on.

As part of our educational efforts, we decided to create several questionnaires looking at the variety of root contributors to mental and emotional distress. That involved going to PubMed and searching for “depression and risk factor,” “ADHD and risk factor” and so on.

We were honestly surprised to find thousands and tens of thousands of studies—leading us to distill down and summarize what we learned in these surveys. Feel free to share them with anyone who might be benefitted!

So there you have it: the world around us seems to be playing a role in what we’re feeling and thinking. Not too surprising, right? By paying attention to all these contributors to mental and emotional distress, who knows? Maybe that will even change how we respond to them.

On to the final lesson!

Lesson 15. Considering the full range of options

If there’s a wide range of factors contributing to mental and emotional distress, that means there is a wide range of ways to support recovery too! Rather than relying on one solution alone, people who find deeper healing often explore a broader menu of supports (relational, behavioral, environmental, spiritual and sometimes medical)—moving forward step by step over time.

Lesson 15, Part 1

Lesson 15, Part 2

Lesson 15, Part 3

Review:

If lots of things contribute to mental/emotional distress, then maybe there are also lots of things to do about it!

Whatever the problem, then, there are likely a range of ways to respond.

Small changes can turn out to be BIG!

Reflection + Discussion:

Why can appreciating the reality of multiple risk factors feel strangely hopeful instead of discouraging?

What happens to people’s sense of agency when they realize there are many possible supports—not just medication or therapy alone?

What kind of life adjustments have you found help lift your own mood? (sleep, movement, food adjustments, sunlight, connection, quiet, reading, prayer)?

How would it feel to start to get more curious about these lifestyle areas (for instance, how much do you ‘get out’ into the natural world? How much movement do you get in an average day?)

How do you balance urgency for relief now with patience for real, lasting change?

Where do you see resistance to change show up most—fear, overwhelm, habit, convenience, identity, or something else?

If you were building a realistic “All of Life” wellness plan, what 2–3 areas would you start with first—and why?

And there you have it, All of Life! You made it to the end. Now all you have left is your own life ahead of you....Oh yes, and there’s some concluding words from us.

A few tips on developing your ‘Wellness Recovery Action Plan’

If it’s true that many things contribute to mental and emotional distress, then the good news is there’s lots of things we can start to look at adjusting that might make a difference. In the previous Lesson 14, we referred you to several vulnerability questionnaires we’ve developed for depression and ADHD that help someone explore the particular risk factors in their situation. We’ve done some work on other inventories for Postpartum Depression, Anxiety, Bipolar Disorder, and Schizophrenia.

Once we pay attention to the variety of contributors to mental and emotional distress, we can begin to create our own personalized plan—a unique and comprehensive plan specific to our personal or family (or child’s) situation that includes any adjustment that feels important for us to consider. If you’re interested in doing that, here are some basic steps to consider:

(1) Review and inventory anything that might be contributing to you or your child’s current mental or emotional state. This can include hunches you’ve had, as well as issues that other professionals or family members may have brought up. If you’re facing depression or ADHD, one of our vulnerability inventories mentioned in the last lesson may be helpful.

(2) Once you have a list of all the potential contributors in your situation, it’s time to lay out a plan. Take out two pieces of paper, labeling one “Short-term plan” and the other “Long-term plan.” For your short-term plan, sketch out anything that feels important to do in the next three months. Just like you would do if you had the flu, your short-term plan should include any special self-care that needs to happen immediately. If not chicken noodle soup and lots of rest, what is the equivalent for mental and emotional distress? Is there anything you or your loved one needs NOW that could really help decrease the stress of this experience and begin to stimulate healing?

Trust your gut on these plans. Write items that come to you, and put them in the place that feels right (short or long-term). Keep these papers close to you in case other ideas come to you, or if others you trust have good suggestions. In these suggestions, we thank Mary Ellen Copeland for her pioneering work in developing what she calls “Wellness Recovery Action Plans.”

For the long-term plan, list actions that feel important to put into place later on, but not necessarily over the next couple of months. This longer-term plan is about achieving a sustainable and stable wellness over time.

(3) As you begin to put your plans into place, be willing to improve and upgrade them over time—even as you “stick with” what feels important to practice and change. Get others you love and trust involved, including family members, and professionals who are supporting you.

Let me know how it goes! I’d love to hear about your experience.